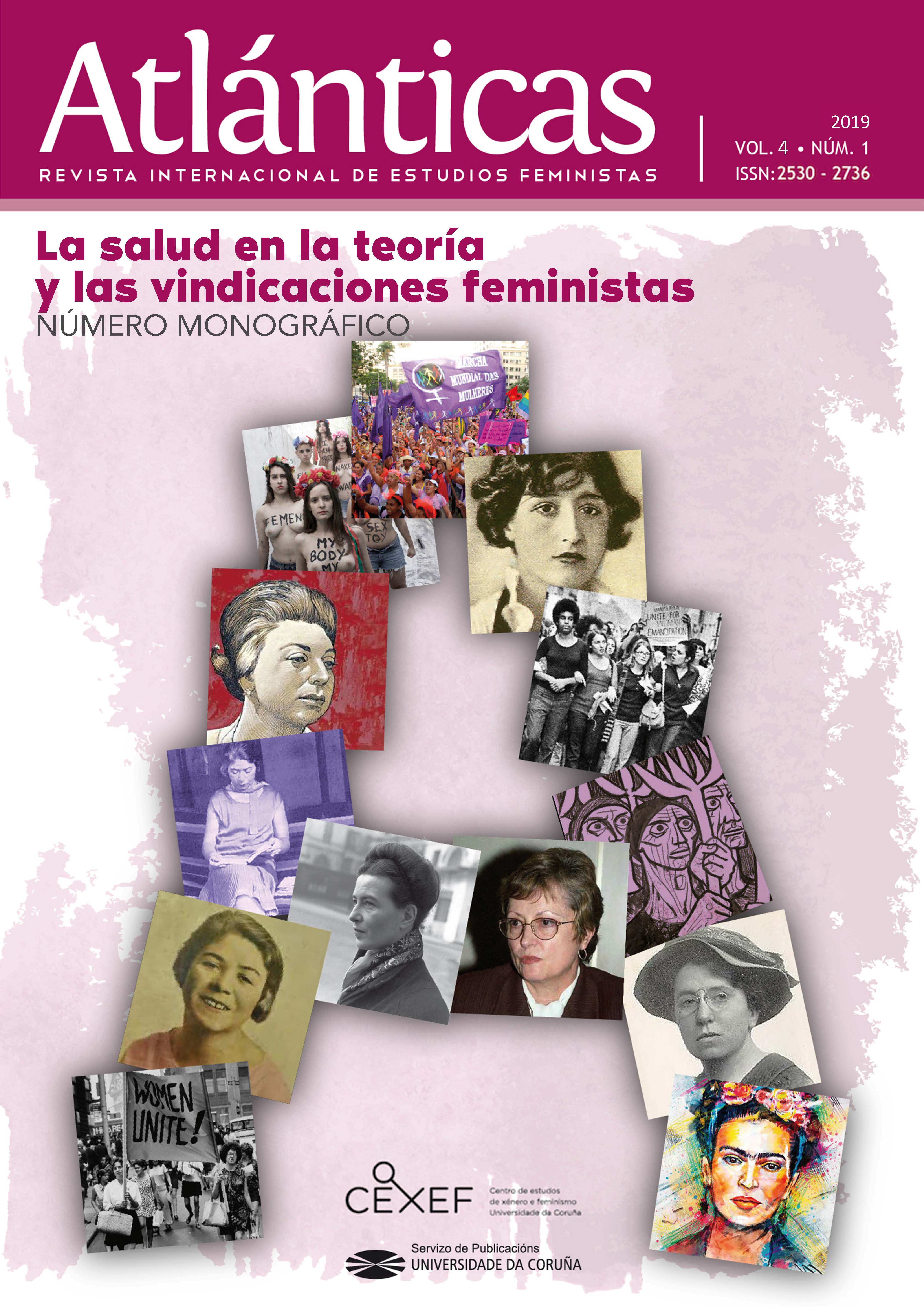

Elementos para la despolitización del cáncer de mama

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.17979/arief.2019.4.1.5733Palabras clave:

feminismo, cáncer de mama, salud de las mujeres, empoderamientoResumen

El cáncer de mama ha cobrado una visibilidad sin precedentes en el Estado español. Tras unos orígenes preocupados por el carácter opresivo del rol de la paciente y los determinantes sociales de la incidencia del cáncer, las últimas tres décadas se han caracterizado por una preocupación con el diagnóstico temprano de la enfermedad a través de programas de cribado y de campañas solidarias de concienciación. A priori parece que habría que festejar esta politización progresiva del cáncer de mama que lo ha puesto en la agenda nacional. En este articulo argumento que lo político ha entrado en crisis, despolitizando la enfermedad sin tan apenas levantar sospechas entre los sectores más críticos del país, incluido el feminista. Retomo la crítica de la ‘sobreinvisibilización’ del cáncer de mama de la antropóloga vasca Mari Luz Esteban (2017) para demostrar cómo nos encontramos en una situación en la que la premisa ‘el fin justifica los medios’ ha colonizado el pensamiento colectivo. Esta colonización limita la capacidad de las instituciones, personas, organizaciones, profesionales y corporaciones de hacer autocrítica. No planteamos cuestiones entorno a qué temas se abordan, cómo se habla de la enfermedad, cómo se representa a las mujeres y qué temas permanecen silenciados o tabú. Para ilustrar la despolitización presentaré ejemplos de los dos elementos que componen la sobreinvisibilización: los discursos y prácticas sobre el cáncer de mama hipervisibles y aquellos que son invisibilizados. Los primeros son dominantes, monotemáticos y perpetúan mensajes androcéntricos. Los invisibilizados raramente llegan al ámbito público, principalmente porque cuestionan el estatus quo de la industria del cáncer.

Descargas

Referencias

Alguacil, Juan (2015). ¿Trabajar puede provocar cáncer? Retrieved 13 February 2019, from Mejor Sin Cáncer website: https://mejorsincancer.org/2015/05/14/trabajar-puede-provocar-cancer

Arias, Samuel A. (2009). Inequidad y cáncer: Una revisión conceptual. Rev. Fac. Nac. Salud Pública, 27(3), 341-348.

Aronowitz, Robert. A. (2001). Do not delay: Breast cancer and time, 1900–1970. Milbank Quarterly, 79(3), 355-386. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.00212

Bessie, Adam; Sulik, Gayle & Parenteau, Marc (2017). The perfect cancer patient. Retrieved from https://narratively.com/im-not-the-perfect-cancer-survivor-but-ive-learned-to-live-with-that

Boston Women’s Health Book Collective (1971). Our bodies, ourselves: A book by and for women. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Brenner, Barbara (2000). Sister support: Women create a breast cancer movement. In Anne Kasper & Susan J. Ferguson (Series Ed.), Breast cancer: Society shapes an epidemic (pp. 325–354). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Broom, Dorothy (2001). Reading breast cancer: Reflections on a dangerous intersection. Health:, 5(2), 249-268. https://doi.org/10.1177/136345930100500206

Brunner, Eric (1997). Socioeconomic determinants of health: Stress and the biology of inequality. BMJ, 314(7092), 1472. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.314.7092.1472

Carson, Rachel (1962). Silent Spring. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Costas-Caudet, Laura (2015). 10 consejos para prevenir el cáncer en tu día a día—Mejor Sin Cáncer. Retrieved 12 February 2019, from Mejorsincaner.org website: https://mejorsincancer.org/2015/04/15/10-consejos-para-prevenir-el-cancer-en-tu-dia-a-dia

Davis, Devra L. (2004). When smoke ran like water: Tales of environmental deception and the battle against pollution. New York, NY: Basic Books.

De Michele, Grazia (2016). Radical objects: ‘Cancer sucks’. History Workshop Online. Retrieved from http://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/radical-objects-cancer-sucks

Ehrenreich, Barbara (2001). Welcome to cancerland. Retrieved 26 August 2013, from Harper’s Magazine website: http://harpers.org/archive/2001/11/welcome-to-cancerland

Elliott, Charlene (2007). Pink!: Community, contestation, and the colour of breast cancer. Canadian Journal of Communication, 32(3). Retrieved from http://cjc-online.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/1762

Engel, Connie L.; Rasanayagam, Sharima M.; Gray, Janet M. & Rizzo, Jeanne (2018). Work and Female Breast Cancer: The State of the Evidence, 2002–2017. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 28(1), 55-78.

Epstein, Julia J. (1986). Writing the unspeakable: Fanny Burney’s mastectomy and the fictive body. Representations, 16, 131-166.

Escribà-Agüir, Vicenta & Fons-Martinez, Jaime (2014). Crisis económica y condiciones de empleo: Diferencias de género y respuesta de las políticas sociales de empleo. Informe SESPAS 2014. Gaceta Sanitaria, 28, 37-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2014.01.013

Esteban, Mari Luz (2017). Prólogo. Cáncer de mama: La rebelión feminista no ha hecho más que empezar. In Cicatrices (invisibles). Perspectivas feministas sobre el cáncer de mama (pp. 13-20). Barcelona: Bellaterra.

Forcades i Vila, Teresa (2017). Cáncer y negocio: Consideraciones éticas. MyS. Mujeres y Salud, (42), 32-34.

Goldenberg, Maya (2010). Working for the cure: Challenging pink ribbon activism. In Roma Harris, Nadine Wathen, & Sally Wyatt (Series Ed.), Configuring Health Consumers: Health Work and the Imperative of Personal Responsibility (pp. 140-159).

Hill, Sharon (2018). Study breast cancer cases at bridge, says customs union and researcher | Windsor Star. Windsor Star (Canada). Retrieved from https://windsorstar.com/news/local-news/investigate-breast-cancer-cases-at-ambassador-bridge-says-customs-union-and-researcher

Hodge Mccoid, Cathy (2004). Why is prevention not the focus for breast cancer policy in the United States rather than high-tech medical solutions. In Arachu Castro & Merril Singer (Eds.), Unhealthy health policy (pp. 351-362). New York: Oxford AltaMira Press.

HuffPost UK. (2012). Mel B reveals cancer scare as she goes topless for breast cancer charity Coppafeel. Retrieved 13 February 2019, from HuffPost UK website: https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2012/09/12/mel-b-cancer-scare-cosmopolitan_n_1876592.html

Inhorn, Maracia C. & Whittle, K. Lisa. (2001). Feminism meets the “new” epidemiologies: Toward an appraisal of antifeminist biases in epidemiological research on women’s health. Social Science & Medicine, 53(5), 553-567.

Irueta, Ainhoa (2017). Autobiografía de una marimacho cancerosa. In Porroche Escudero, Ana; Coll-Planas, Gerard & Caterina Ribas (Eds.), Cicatrices (in)visibles. Perspectivas feministas sobre el cáncer de mama (pp. 181-190). Barcelona: Bellaterra.

Jacobs, Miriam & Dinham, Barbara. (2003). Silent invaders: Pesticides, livelihoods, and women’s health. London; New York; New York: Zed Books in association with Pesticide Action Network UK ; Distributed in the USA exclusively by Palgrave.

Johnson, Robin E. (2011). Cancer disparities: An environmental justice issue for policy makers. Environmental Health Policy. Physicians for Social Responsibility. Psr.org.

Kasper, Anne S. & Ferguson, Susan. J. (Eds.). (2000). Breast Cancer: Society Shapes an Epidemic. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Kaufert, Patricia (1996). Women and the debate over mammography: An economic, political and moral history. In Carolyn Sargent & Caroline Brettel (Eds.), Gender and Health: An International Perspective (pp. 167-186). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

King, Samantha (2001). Marketing Generosity: Avon’s Women’s Health Programs and New Trends in Global Community Relations. (Research Paper). International Journal of Sports Marketing & Sponsorship, 3(3), 267.

King, Samantha (2006). Pink ribbons, Inc. Breast cancer and the politics of philanthropy. Retrieved from http://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/pink-ribbons-inc

King, Samantha (2010). Pink diplomacy: On the uses and abuses of breast cancer awareness. Health Communication, 25(3), 286-289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410231003698960

Klawiter, Maren (2008). The biopolitics of breast cancer: Changing cultures of disease and activism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Lerner, Barron H. (2001). The breast cancer wars: Hope, fear, and the pursuit of a cure in twentieth-century America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lerner, Barron H. (2003). ‘To see today with the eyes of tomorrow’: A history of screening mammography. Canadian Bulletin of Medical History/Bulletin Canadien d’histoire de La Médecine, 20(1), 299-321.

Ley, Barbara L. (2009). From pink to green disease prevention and the environmental breast cancer movement. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Lock, Margaret & Nguyen, Vinh-Nguyen. (2010). An Anthropology of Biomedicine. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Lorde, Audre (1992). The cancer journals. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Lynn, Helen (2007). Politics and Prevention: Linking breast cancer and our environment. Utrecht: : Women in Europe for a Common Future.

McArthur, Jane E. (2014). The Toronto Star and the politics of breast cancer (MA, University of Windsor). Retrieved from https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/5033

McArthur, Jane E. (2019). As the oceans rise, so do your risks of breast cancer. Retrieved 12 February 2019, from The Conversation website: http://theconversation.com/as-the-oceans-rise-so-do-your-risks-of-breast-cancer-108420

Mujerhoy (2010). Por segundo año consecutivo, Ausonia y la Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer ponen en marcha una nueva campaña contra el cáncer de mama de Ausonia. Retrieved 13 February 2019, from Mujerhoy website: https://www.mujerhoy.com

O’Neill, Rory & Qasrawi, Jawad. (2007). Hazards work cancer prevention kit. Retrieved from Stirling University’s Occupational and Environmental Health and Safety Research Group website: http://www.hazards.org/cancer/preventionkit/index.htm

Porroche-Escudero, Ana (2013). Luces y sombras de la reconstrucción mamaria. MyS. Mujeres y Salud, 34-35, 30-33.

Porroche-Escudero, Ana (2014). Perilous equations? Empowerment and the pedagogy of fear in breast cancer awareness campaigns. Women’s Studies International Forum, 47, Part A, 77-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2014.08.003

Porroche-Escudero, Ana (2015a). Beatriz Figueroa: Relinking cancer treatments, incapacity to work, the social security system, and patients economic rights. Breast Cancer Consortium Quarterly, 4. Retrieved from http://breastcancerconsortium.net/beatriz-figueroa-relinking-cancer-treatments-incapacity-work-social-security-system-patients-economic-rights

Porroche-Escudero, Ana (2015b). La violencia de la cultura rosa. Las campañas de concienciación de cáncer de mama. 37, 32-35.

Porroche-Escudero, Ana (2016). Empoderamiento: El Santo Grial de las campañas de salud pública sobre el cáncer de mama. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 74(2), e031.

Porroche-Escudero, Ana & Figueroa, Beatriz. (2016). Drets econòmics de les persones afectades de càncer. In Porroche-Escudero, Ana; Coll-Planas, Gerard & Caterina Ribas (Eds.), Cicatrius (in)visibles Perspectives feministes sobre el càncer de mama (pp. 175-186). Barcelona: Bellaterra.

Romano Mozo, Dolores (2012). Disruptores endocrinos Nuevas respuestas para nuevos retos. Instituto Sindical de Trabajo, Ambiente y Salud (ISTA).

Sandell, Kerstin (2008). Stories without significance in the discourse of breast reconstruction. Science, Technology & Human Values. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243907306693

Sulik, Gayle (2012). Pink ribbon blues: How breast cancer culture undermines women’s health. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sulik, Gayle & Zierkiewicz, Edyta (2014). Gender, power, and feminisms in breast cancer advocacy: Lessons from the United States and Poland. Journal of Gender and Power, 1(1), 111-145.

Sumalla, Eric. C.; Castejón, Vanessa; Ochoa, Cristian & Blanco, Ignacio. (2013). ¿Por qué las mujeres con cáncer de mama deben estar guapas y los hombres con cáncer de próstata pueden ir sin afeitar? Oncología, disidencia y cultura hegemónica. Psicooncología, 10(0), 7-56.

Taboada, Leonor (1978). Cuaderno feminista. Introducción al Self- Help. Barcelona: Fontanella.

Valls-Llobet, Carme (2006). Factores de riesgo para el cáncer de mama. MyS. Mujeres y Salud, 18, 16-20.

Valls-Llobet, Carme (2010). Contaminación ambiental y salud de las mujeres. Investigaciones Feministas, 1(0), 149-159.

Valls-Llobet, Carme (2017). Influencia de la salud laboral y el medio ambiente en el cáncer de mama. In Cicatrices (in)visibles. Perspectivas feministas sobre el cáncer de mama (pp. 83–92). Barcelona: Bellaterra.

Vandenberg, Laura N. (2019, February 7). It’s time to talk about cancer prevention—EHN. Retrieved 12 February 2019, from Environmental Health News website: https://www.ehn.org/laura-n-vandenberg-its-time-to-talk-about-cancer-prevention-2628192178.html

Whitehead, Margaret (2007). A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 61(6), 473-478.

Wilkinson, Sue (2001). Breast cancer: Feminism, representations and resistance – a commentary on Dorothy Broom’s ‘Reading breast cancer’. Health:, 5(2), 269-277.

Yadlon, Susan (1997). Skinny women and good mothers: The rhetoric of risk, control, and culpability in the production of knowledge about breast cancer. Feminist Studies, 23(3), 645-677.

Zavestoski, Stephen; McCormick, Sabrina & Brown, Phil (2004). Gender, embodiment, and disease: Environmental breast cancer activists’ challenges to science, the biomedical model, and policy. Science as Culture, 13(4), 563-586.

Zones, Jane S. (2000). Profits from pain: The political economy of breast cancer. In Susan J. Ferguson & Anne S. Kasper (Eds.), Breast cancer: Society shapes an epidemic (pp. 119-151). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Descargas

Publicado

Número

Sección

Licencia

Los y las autores/as ceden todos los derechos, título y materiales contenidos en el trabajo aceptado a la Revista Atlánticas, quien podrá publicar en cualquier lengua y soporte, divulgar y distribuir su contenido total o parcial por todos los medios tecnológicamente disponibles y a través de repositorios.

Se permite y se anima a los y las autores/as a difundir los artículos aceptados para su publicación en los sitios web personales o institucionales, ante y después de su publicación, siempre que se indique claramente que el trabajo pertenece a esta revista y se proporcionen los datos bibliográficos junto con el acceso al documento.

Los trabajos publicados en esta revista están bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-Compartir Igual 4.0. Internacional. Usted es libre de:

- Compartir — copiar y redistribuir el material en cualquier medio o formato

- Adaptar — remezclar, transformar y crear a partir del material para cualquier finalidad, incluso comercial.

Reconocimiento — Debe reconocer adecuadamente la autoría, proporcionar un enlace a la licencia e indicar si se han realizado cambios<. Puede hacerlo de cualquier manera razonable, pero no de una manera que sugiera que tiene el apoyo del licenciador o lo recibe por el uso que hace.

CompartirIgual — Si remezcla, transforma o crea a partir del material, deberá difundir sus contribuciones bajo la misma licencia que el original.

En relación con la incusión de los artículos, reseñas y entrevistas en repositorios debemos señalar lo siguiente:

a) Se autoriza sólo a subir la copia post-print del editor, es decir, la última versión qeu fue publicada, con el mismo formato y apariencia. Los derechos sobre el documento deben mantenerse respecto de la publicación original.

b) Sólo se autorizará el alojamiento en repositorios y plataformas gratuítos, que no cobren ni por el alojamiento ni por la consulta o obtención de documentos.

c) En el repositorio o plataforma dónde se aloje, el documento debe identificarse con los datos completos de publicación de esta copia post-print, lo que incluye su DOI cuando lo tuviese.

d) En ese documento ya tiene un alojamiento electrónico en una revista OJS o en el RUC de la UDC, es deseable incluír un vínculo en el nuevo repositorio o plataforma, y no alojar el documento en si (esto facilita la visibilidad del RUC y las revistas de la UDC, la ayuda a revalorizar los libros y revistas hechos por el profesorado). Si esta opción no es vialbe, se podrá alojar el documento, pero siempre identificándolo con datos completos de publicación (lo que incluye su DOI, en caso de tenerlo).